A series of five articles on circles.

2) Geometry: Circles and Angles

4) Inscribed and Circumscribed Circles and Polygons

5) Slicing up Circles: Arclengths, Sectors, and Pi

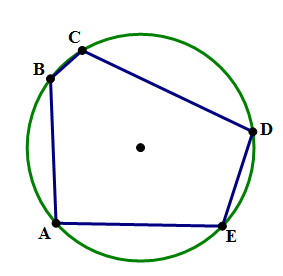

One more sophisticated type of geometric diagram involves polygons “inside” circles or circles “inside” polygons. When a polygon is “inside” a circle, every vertex must lie on the circle:

In this diagram, the

Notice, now, that each side of this irregular pentagon is tangent to the circle. Now, the pentagon is circumscribed around the circle, and the circle is inscribed in the pentagon. In both cases, the outer shape circumscribes, and the inner shape is inscribed.

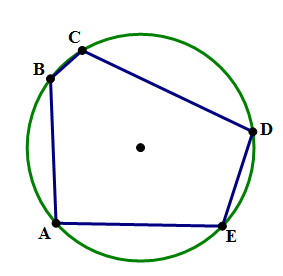

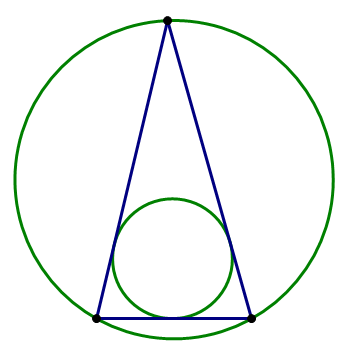

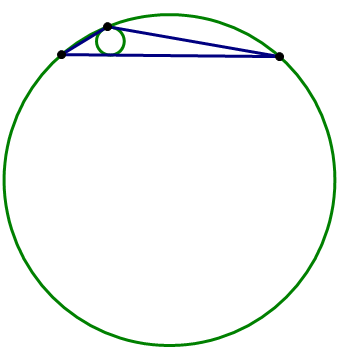

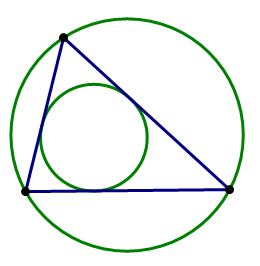

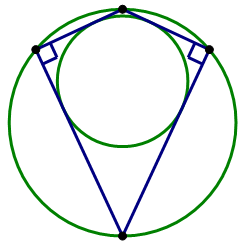

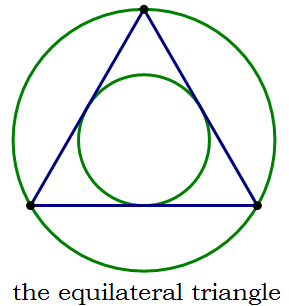

As is the case repeatedly in discussions of polygons, triangles are a special case in the discussion of inscribed & circumscribed. Every single possible triangle can both be inscribed in one circle and circumscribe another circle. That “universal dual membership” is true for no other higher order polygons —– it's only true for triangles. Here's a small gallery of triangles, each one both inscribed in one circle and circumscribing another circle.

Notice that, when one angle is particularly obtuse, close to

Many quadrilaterals can be neither inscribed in a circle nor circumscribed by a circle: that is it say, it is impossible to construct a circle that passes through all four vertices, and it is also impossible to construct a circle to which all four sides are tangent.

Some quadrilaterals, like an oblong rectangle, can be inscribed in a circle, but cannot circumscribe a circle. Other quadrilaterals, like a slanted rhombus, circumscribe a circle, but cannot be inscribed in a circle.

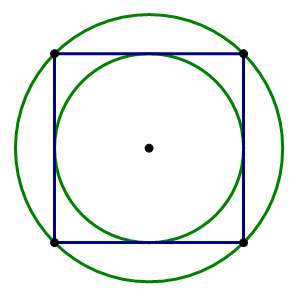

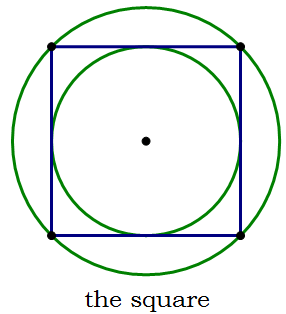

An elite few quadrilaterals can both circumscribe one circle and be inscribed in another circle. Of course, the square (below, left), the most elite of all quadrilaterals, has this property. Another example is the “right kite” (below, right), a kite with a pair of opposite right angles:

While this “dual membership” is true for all triangles, it's limited to some special cases with quadrilaterals.

What was true for quadrilaterals is also true for all higher polygons.

That last category, the elite members, always includes the regular polygon. Just as all triangles have this “dual membership”, so do all regular polygons. Here's a gallery of regular polygons, with both their inscribed circle and their circumscribing circle.

Obviously, as the number of sides increases, the sizes of the two circles become closer and closer.

QUANT questions about inscribed and circumscribed polygons are rare, and may test both your understanding of terminology and your visualization skills by describing the geometric situation (e.g. “rectangle JKLM is inscribed in a circle”) and not giving you a diagram.

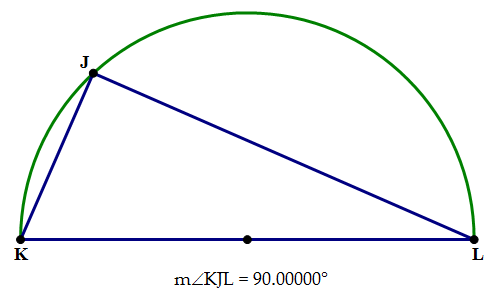

This is one special case the QUANT loves. It could easily appear somewhere on the Quant section of your real QUANT.

If all you know is that KL is the diameter of the circle, that's sufficient to establish that

Q1. In the diagram above,

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

Q1. First of all,

Answer = B