Function Introduction

Consider these two practice Quantitative problems:

1. Given f(x) = 3x - 5, for what value of x does 2*f(x) - 1 = f(3x - 6)

(A) 0

(B) 4

(C) 6

(D) 7

(E) 13

2. Given f(x)={\dfrac{x}{x+1}}, for what value k doess {\Large{f}}\Big(f(k)\Big)={\dfrac{2}{3}}

(A) -2

(B) \dfrac{5}{3}

(C) 1

(D) 2

(E) 8

3. If f(x) = 12 - \dfrac {x^2}{2} and f(2k) = 2k, what is one possible value for k?

(A) 2

(B) 3

(C) 4

(D) 6

(E) 8

If you find these questions completely incomprehensible, then you have found the right page.

Function notation

The Quantitative section will ask an occasional question about function notation. Here is a basic catechism about functions and what you need to know about them for the QUANT.

What is a function?

A function is a rule, a “machine”, that takes an input and gives an output. When we are told the equation of a function, that equation makes explicit the rule this particular function is following. For example, for the function f(x) = 3x - 5, the rule is: whatever input x you give — and that input could be any real number — this function will multiply this input by 3 and then subtract five from the product: that difference is the output. If I put in an input of x = 2, then I get an output of 3(2) - 5 = 1, and the way we compactly write that fact with function notation is: f(2) = 1. In other words, an input of 2 gives an output of 1.

Notice — this is a very subtle issue. The x that appears in the equation of a function is a different sort of variable than the ordinary x of solve-for-x algebra. This x is what one might call a “formula variable”, like the a, b, and c in the quadratic formula. In other words, the x of function notation is not an x that is equal to only a single value; rather, it can be set equal to any value, any real number on the number line, when we want to plug that number into the function.

Typical misunderstandings of function notation

When we write f(x), many people new to function notation will misinterpret this as multiplication — as if there’s a thing “f” times the variable “x”. That is 100% incorrect. A function is a process through which the input goes. Cooking is a process through which food goes. Puberty is a process through which people go. A function is a process acting on the number, and the nature of that action is outside the categories of simple arithmetic actions (add, subtract, multiply, divide).

Relatedly, the parentheses of function notation are mathematically inviolable. Nothing may pass through these parentheses. Again, this can be anti-intuitive, because when parentheses are used in ordinary notation, you can distribute through parenthesis, factor out, etc. Because a function is a different category of mathematical object, its parentheses are of a different nature. Thus

\color{red}f(x+5) \not = f(x) + 5

\color{red}f(x-5) \not = f(x) - 5

\color{red}f(5*x) \not = 5*f(x)

\color{red}f({\dfrac{x}{5}}) \not = {\frac{f(x)}{5}}

\color{red}f(x^2) \not = {[f(x)]}^2

If you can simply avoid these mistakes and respect at all times the inviolability of the function’s parentheses, you will already be in better shape than a sizable portion of QUANT test takers.

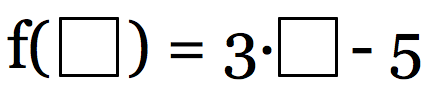

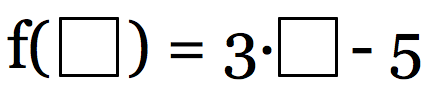

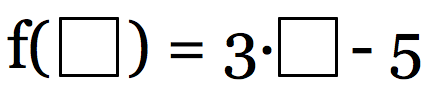

How a mathematician thinks about a function

In the above section, I discussed ways that folks new to functions might misinterpret function notation. Now, I am going to discuss how functions are seen by people who really understand them. Suppose we have the function f(x) = 3x - 5. Here’s what a mathematician looking at this function sees:

Where folks new to function just see the letter x, mathematicians see a “box”, an empty slot, a space that is, in some ways, analogous to an artist’s blank canvas. Anything that get plugged into the box on the left needs to get plugged into the box on the right. We can plug in numbers — any of the continuous infinity of real numbers on the real number line. We can also plug in algebraic expressions: If I put (2x + 7) into the box on the left, I need to put that exact identical expression into the box on the right. I can even put whole functions — the same function or an entirely different function — into the boxes. In fact, the list of mathematical objects that can be plugged into a function extends into far more sophisticated mathematical objects (matrices, differential operators, etc.) that are well beyond the realm of Quant. The QUANT, though, will expect you to know what to do if they give you, say, the function f(x) = 3x - 5, and then ask you, say, to plug in the expression 2x + 7:

f(2x + 7) = 3*(2x + 7) - 5 = 6x + 21 - 5 = 6x + 16

Summary

If this is your first time encountering, or first time understanding, function notation, it is a worthwhile topic to practice, so that you are comfortable with it by test day. If you feel you have learned something from this, go back and try those two practice problems again before reading the solutions below.

Practice problem explanations

1. We have the function f(x) = 3x - 5, and we want to some sophisticated algebra with it. Let’s look at the two sides of the prompt equation separately. The left side says: 2*[f(x)] - 1 — this is saying: take f(x), which is equal to its equation, and multiply that by 2 and then subtract 1.

2*[f(x)] - 1 = 2*(3x - 5) - 1 = 6x - 10 - 1 = 6x - 11

The right side says f(3x - 6) — this means, take the algebraic expression (3x - 6) and plug it into the function, as discussed above in the section “How a mathematician things about a function.” This algebraic expression, (3x - 6), must take the place of x on both sides of the function equation.

f(3x - 6)= 3*[3x - 6] - 5 = 9x - 18 - 5 = 9x - 23

Now, set those two equal and solve for x:

9x - 23 = 6x - 11

9x = 6x - 11 + 23

9x = 6x + 12

9x - 6x = 12

3x = 12

x = 4

Answer = B

2. There are several ways to approach this problem. One quick way is to notice that if x = 2, f(2) = \dfrac{2}{3}. That’s not the answer, but it gives us a shortcut. If f(k) = 2, then we see that f(f(k)) = f(2) = \dfrac{2}{3}. So, really, finding the value of k that satisfies the prompt equation really simplifies to solving the equation f(k) = 2.

f(k) = \dfrac{k}{(k + 1)} = 2

Multiply both sides by the denominator.

k = {2}*{(k + 1)}

k = 2k + 2

k - 2k = 2

-k = 2

Multiply both sides by -1.

k = -2

answer = A

3. First of all, see this Web Page and check the related lesson linked below for some background on function notation.

We can plug anything in for x and get a result. You can find f(1), for example, by plugging in 1 where x is, and you would get 12 - \dfrac{1}{2} = 11.5. Or we could find f(2), which would be 12 - \dfrac{4}{2} = 10.

So the notation f(2k) means that we are going to plug a 2k in for x everywhere in the formula for f(x). That would be:

f(2k) = 12 - \dfrac {(2k)^2}{2} = 12 - \dfrac {4k^2}{2} = 12 - 2k^2

Remember that we have to square both the 2 and the k, to get 4k^2. Now, this expression, the output, we will set equal to 2k.

12 - 2k^2 = 2k

0 = 2k^2 + 2k - 12

0 = k^2 + k - 6

0 = (k+3)(k - 2)

k = -3 \text { or } k = +2

All the answers are positive, so we choose k = 2.

answer = A