Solve this question. Allot yourself a strict

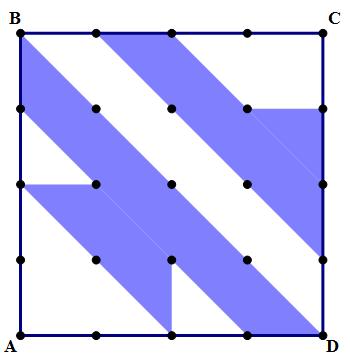

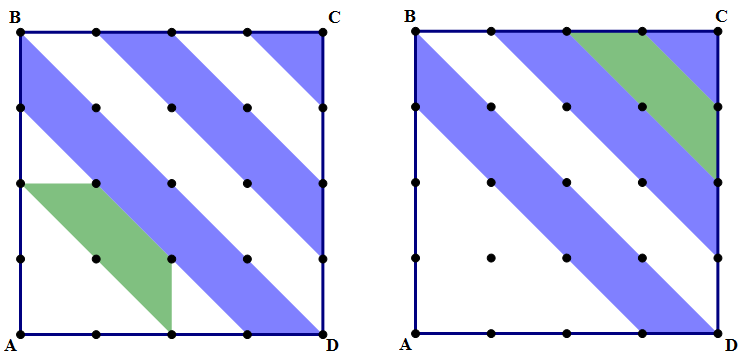

Q1. In the figure, ABCD is a square, and all the dots are evenly spaced: each vertical or horizontal distance between two adjacent dots is 3 units. Find the area of the shaded region.

A. 60

B. 72

C. 81

D. 96

E. 120

Q2. If

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

A.

B.

C.

D.

E.

An explanation will follow below.

Some people find GRE Math hard because they are rusty at math in general: this post is not primarily addressed at those folks, although they may have some aha’s from reading this. There’s no substitute for learning the basic math content you need.

Other people are reasonably comfortable with the math itself, but often complain: “I could do most GRE Quant problems if I had enough time, but I always seem to run out of time.” “I just wish I could do GRE math faster.” Does this sound like something you have said? Then this is precisely the post for you.

First, a quick overview of hemispheric differences in the brain — this will be review for some people. The cerebrum, the “intelligence” part of our brain, is divided into two halves: the left & right hemisphere. These control all the sensation & muscular movements on the opposite side of the body — if you want to move your left leg, it’s the right half of your brain that oversees this task. The two hemispheres also process information very differently. Here is a brief overview of hemispheric difference: notice which set of skills feels more comfortable, more natural to you.

The left hemisphere is about logic, organization, precision, and detail management. It specializes in differentiation, that is, telling the exact difference between closely related things. It’s very good at following clear rules, recipes, formulas, and procedures in a step-by-step logical way. The left brain controls the grammar and syntax of language, the formal, almost “mathematical”, side of language. If I were to say, “I are happy,” it would be your left brain that recognizes this as wrong.

The right hemisphere is intuition and pattern-matching. It specializes in integration, that is, seeing the underlying similarity or unity behind seemingly distinct things. We dream in the right brain. The right brain is responsible for myth, poetry, analogy and metaphor. It is often called the “artistic” side of the brain. It is good at information presented as symbols or images. It is good at facial recognition and voice recognition (notoriously hard problems for computers!) The left brain does grammar and syntax, but the right brain controls a very different side of language: emotional inflection, body language, innuendo and implication. If person A says “Today is a great day!” in a completely bright and bubbly way in all sincerity, and then person B says “Today is a great day!” in a way that is absolutely dripping with bitter sarcasm — then, according to the left brain, exactly the same thing was said twice (same grammar, same syntax, etc.); it’s only the right brain that senses the profound emotional difference between those two statements.

Most folks are naturally dominant in one of the two hemispheres. There is some association with handedness and hemispheric dominance: left-handed people are slightly more likely to be right-brain dominant. The extreme left-brain folks are hyper-organized and methodical, for example, an accountant. The extreme right-brain people are the wild artsy folks, or folks who live from one leap of intuition to the next.

Which hemisphere is better for math? Well, the detail-management and organization and precision of the left-brain are a huge help in arithmetic and algebra. Geometry is the only branch of math in which the right-brain pattern-matching skills can play some role. In general, left brain folks usually feel reasonably comfortable with math, and certainly can follow the methodical procedures with ease. Typically, the right brain folks tend to have a difficult time keeping all the details straight, although many times they tune into the “big picture” ideas faster.

Those are tendencies, but success in math — and in fact, success in almost anything that challenges our intelligence — involves developing both sides of the brain. One of the reasons Leonardo de Vinci is often regarded as one of the smartest people ever to walk the earth is because he demonstrated strong skills of both hemispheres.

What does this mean for your GRE Quant performance? Well, if you are a typical right brain person, you probably need to sharpen your understanding of all the rules and all the details, and learn to manage details with precision. That’s something that comes with practice, practice, practice.

Now, for the left-brain folks: you probably know the rules reasonably well. You probably were generally a “good-at-math” kind of student. Probably, faced with most GRE Quant questions, you could figure out the right answer, given enough time. The catch, of course, is that you don’t have unlimited time on the GRE: just 40 minutes for 25 questions, or a little more than 90 seconds per question.

An overwhelming number of GRE Quant are designed specifically to punishing someone who is overly left-brained. In other words, they are designed so that if you take the methodical, step-by-step plodding approach, then yes, you would eventually reach the answer, but it would take you a very long time. Whenever that’s the case in a question, there’s always a way to reframe the question, so that the solution becomes very quick, sometimes almost immediate.

Whenever you see yourself starting out on a very straightforward, step-by-step, long haul calculation, stop yourself. This is always the challenge for left brain folks, but you have to re-frame the question, to understand the task from a different angle. You are looking for the “Leonardo da Vinci” solution to the problem.

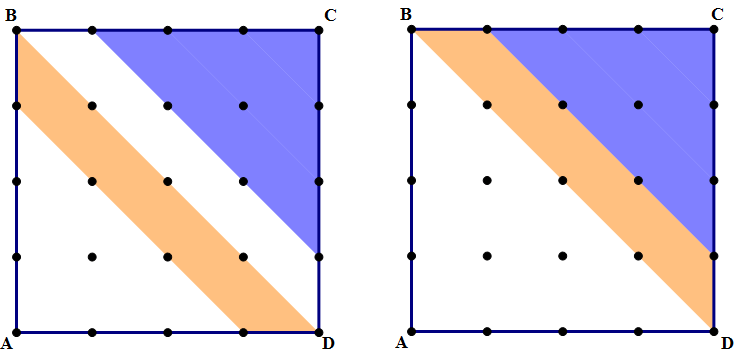

Q1. Here, I will demonstrate with the practice problem. Yes, you could figure out separately the area of each triangle, each square, each trapezoid, and then add all those shapes together. That would take some time. Here’s a right brain solution to this question — rearrange the pieces!

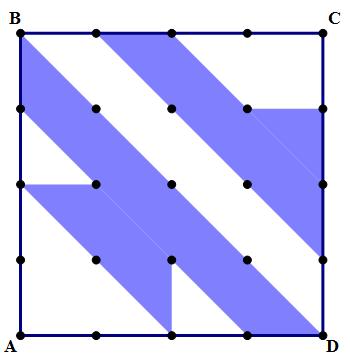

First, slide the red piece up.

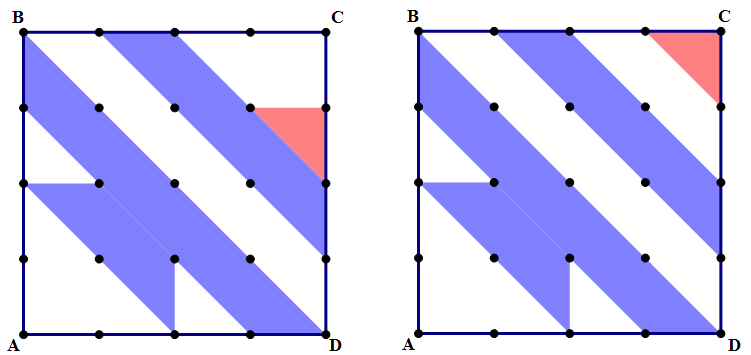

Now, slide the green piece into that blank space.

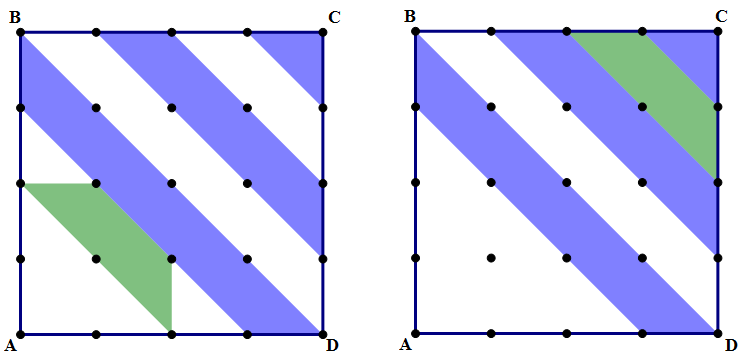

Now, flip the orange piece over diagonal BD.

Lo and behold! The shaded region accounts for exactly half the area of the big square. The big square is

Answer = (B).

Once you see the trick, the pattern, there is only the most minimal of calculations needed.

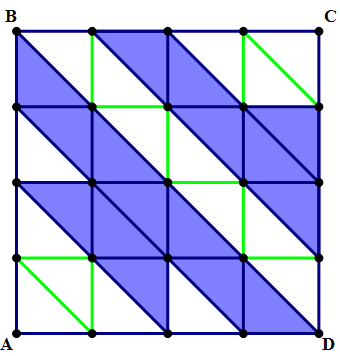

BTW, another reasonably quick right-brain approach would be simply to count all the little triangles.

The original shaded figure can be broken into 16 equal triangles. The full square is 16 little squares, or 32 triangles. Therefore, the area of the shaded figure is exactly half the area of the square.

Some right-brain readers might revel in such solution. Meanwhile, some left-brain folks might be frustrated or annoyed at this point: “Great! Now that it’s pointed out, yes, that’s an efficient way to solve, but how am I supposed to see that on my own?”

Mastering the strengths and skills of your non-dominant hemisphere is never an easy task, but it can be done.

There are a wild variety of things one can do to enhance right-brain function. Read poetry. Look at art. Make art. Read about patterns in comparative mythology. Free-associate. Imagine. Follow chains of word associations. Slow down and really look at things. For example, everyone in the world has seen and could recognize Leonardo’s Mona Lisa painting, but have you ever really looked at it? If you stare at it for 15-20 minutes, really just sink into staring at it, you can see every possible human emotion run across that face. The left-brain is relatively quick: OK, Mona Lisa, I know that, done. The right-brain skills take more time to “warm up”, which is why you have to put your left-brain impatience on hold and really take some time with this. I used the Mona Lisa as an example here, but you could use almost any classic image. All of these practices can help a left-brain person, over time, to get more in touch with right brain abilities.

Here is the plan I would recommend for the extreme left-brain thinker who wants to accelerate her or his learning and mastery of the right-brain skills. From this point forward, whenever you practice GRE Quant, first of all, always practice against a strict time limit. Furthermore, the criterion is no longer: did I get the correct answer? No. Even if you got the correct answer, compare your solution to the official solution: if your solution is a slow methodical approach, and the official solution shows a shortcut, then for your purposes, consider this a question you got wrong. For every such question, force yourself to write down, verbally, the nature of the shortcut, and what you should have done to “see” that shortcut. Force yourself to have to put it into words and explain it: that will strengthen your inter-hemispheric connections. As you collect more and more write-ups like this, periodically go back to re-read the collection. Keep doing this consistently, learning from your mistakes, and before you know it, you will start “seeing” the Leonard-da-Vinci solutions to GRE Quant problems!

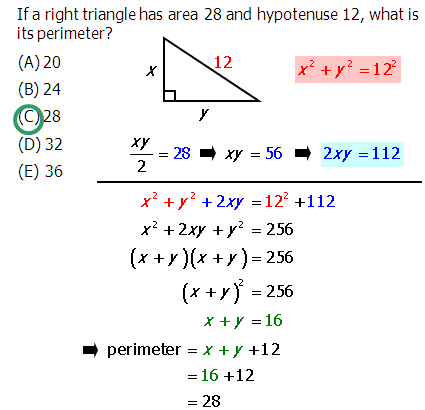

Q2.

Answer = (E).

Q3.

FAQ: Why do we multiply

A: The perimeter would be (leg #1) + (leg #2) + (hypotenuse), or in terms of the numbers and variables we already have,

From the Pythagorean Theorem, we have

So, we want to build

Answer = (C).

FAQ: If

It's a mistake to jump to the conclusion that the only possible values for

A: It's a mistake to jump to the conclusion that the only possible values for

Notice that the question does not state that the numbers have to be integers. So we could easily have a length of